The City of Brooklyn was officially born on April 8, 1834 upon being recognized as a city by the New York State legislature – that quaint body that meets one hundred and fifty miles north of Brooklyn. The new city of Brooklyn would be rapidly transformed into a bustling urban metropolis, and by 860 would be the third largest city in United States.

Brooklyn’s new mayor, John Hall, and the council set about to plan for a suitable edifice to house the business of government. The city fathers of Brooklyn, like their counterparts in other towns and cities, sought to embody Greek and Roman principles in the architecture of the many new town halls and courthouses being erected in the first half of the 19th century. Brooklyn wanted a stately, sober city hall. Two local landowners, Hezekiah Pierrepont and the Remsen family sold a triangular plot of land to the City of Brooklyn. The land was located at Court and Joralemon Streets up the hill from Brooklyn Village at the waterfront. Pierrepont, having earlier bought land from the Remsens for subdivision, hoped that the new city hall location would create a new focus for Brooklyn while also improving the future prospects of the Pierrepont land.

Prior to the 1820’s nearly all of the buildings in the United States were designed by builder-architects. In the early years of the Republic builders worked from English pattern books to erect homes and public buildings. Eventually some of the talented builders, such as Minard Lafever and Benjamin Latrobe created their own designs, essentially becoming self-taught architects. In 1836 William Strickland and Alexander Jackson Davis founded the American Institution of Architects for those builders who wanted to define themselves as ‘professional architects’ who would be able to provide a higher quality service to the public.

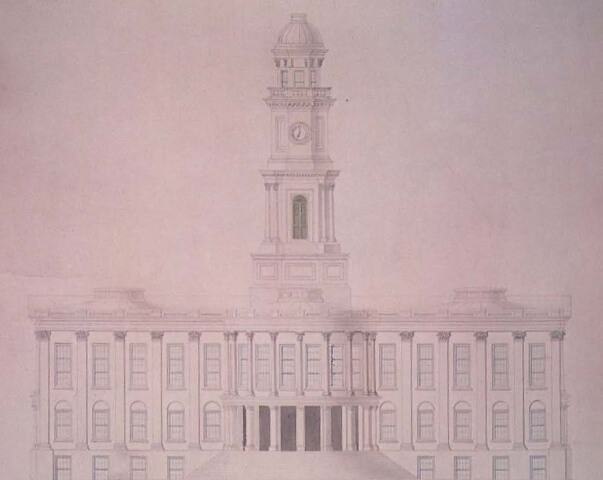

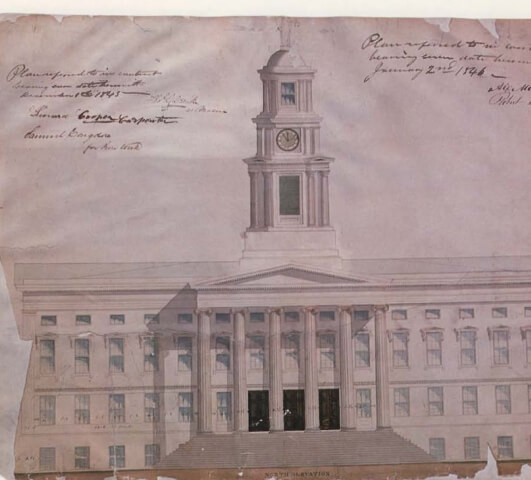

The Brooklyn Common Council, through its Committee for Public Lands and Buildings, established a design competition for the new city hall and offered a $700 prize to the architect of the winning design selected by the Board of Aldermen. The Board reviewed the five submissions and chose a design submitted by Pollard and Johnson. Calvin Pollard was a respected architect with a national reputation. For the competition he teamed up with a temporary partner named Johnson (whose first name has been lost to history). The aldermen also awarded prizes to two runner-up schemes; one by Gamaliel King and the other by Thomas & Company.

Pollard’s initial design was ‘grand’ and ultimately deemed too lavish. He submitted a second scheme, described in the Brooklyn Evening Star as “chaste and beautiful.” Thomas Thomas, one of runner-up architects in the Brooklyn City Hall competition, was from England. He worked as a draftsman, opened his own architectural practice and later took on his two sons as partners. Thomas was part of the first group of architects that formed an association created to differentiate architects from builders. The other runner up was Brooklyn born Gamaliel King, a grocer turned builder-architect. He also served as Director of the Apprentices’ Library and built a Gothic style church near the library. Ultimately, he went on to have his own architectural firm but in 1835, he was not an established architect. King was known as someone with influence in the new city government. Although he did not win the competition, his connections landed him the position of Superintendent and Resident Architect for the new city hall.

The older patrician Pollard could not have liked the appointment of the upstart King to supervise the construction of his design. As soon as the foundation was laid and the cornerstone set in place, an economic depression, known as the Panic of 1837, put a halt to any further construction on Pollard’s building.

In the aftermath of the Panic, Brooklyn was left without a city hall and was besieged with lawsuits, angry architects and stonecutters who had not been paid for their work. Finally, in 1842 the Committee in charge of the building proposed a simple Romanesque Revival two story building topped by a square cupola atop a flat roof.

The public hated the scheme. In reaction to that unpopular design, a local business man, Samuel Johnson, commissioned an illustrator to draw a new plan according to Johnson’s conception. It was a triangular two-story building that filled the entire site with large turrets at the corners. There were to be shops on the ground floor (to help pay for the building) with the city and county offices on the second floor. The Committee liked the idea of revenue, but the scheme was neither feasible or attractive.

In frustration the Council looked at drawings of other architects as well as Calvin Pollard’s original design. Over the next several years other architects submitted new schemes for the city hall, including one by ‘a fellow citizen’ thought to be the work of Richard Upjohn.

By 1845 the city’s newly elected mayor, Thomas Talmadge, was anxious to resolve the city hall problem and avert a possible lawsuit by the stone brokers who were contracted to provide the Tuckahoe marble for the original building. When the construction was halted, the stone brokers were left with tons of cut stone that had not been paid for. They sued the city; and just as the case was about to come to a hearing, Talmadge boldly announced a plan to commission a new city hall and award the building contract to Masterson and Smith, the stone cutters. All that was needed was an architect.

After reviewing all the submitted plans, the Common Council voted to accept the plans of William Ranlett, a New York architect. Ranlett’s scheme was decidedly inferior to Pollard’s original plan. The very next day, after a closed meeting, the council rejected the Ranlett design and requested that Gamaliel King and Henry Grimstead (a Brooklyn architect-builder) submit plans. King’s scheme won by a single vote. Gamaliel King, the home town boy, proved himself to be both a facile designer and a clever politico with friends on the Council.

King’s 1845 scheme undoubtedly owes much to Pollard’s 1835 scheme. It retained the original idea but improved upon Pollard’s design through simplification. King removed the oval room and the half round portico on the north side and replaced it with a Greek style portico and substituted Ionic columns for Pollard’s more expensive Corinthians. Similarly, he echoed the Greek pediment on the sides and rear of the building and enhanced Pollard’s clunkier flat roof. King may have had an edge over the other competitors, but he also proved himself to be the superior talent as well.

Architectural historians can argue over the degree to which Gamaliel King merely adapted Pollard’s design or whether he took a mediocre design and turned it into a memorable building with “elegant severity.” But the fact remains that the final product was a perfect public house for Brooklyn city government. It was handsome but not showy; it was stately but not ostentatious—a perfect embodiment of civic values and democracy.

In the late 1970’s then Borough President Howard Golden established a fund for the restoration of Brooklyn Borough Hall (the former Brooklyn City Hall). Conklin Rossant Architects were selected to produce a master plan and lead the architectural restoration and modernization of systems. It has been reported that after the restoration, Mayor Ed Koch paid a visit to Borough President Golden and wanted to know why the Brooklyn Borough President had a better building than the Mayor of the City.

Gamaliel King would have been proud to hear that!

Existing Conditions

A designated New York City landmark built in 1846-51, Brooklyn Borough Hall, the original City Hall, is one of the most significant government buildings in Brooklyn and is the heart and soul of Brooklyn’s Civic Center.

Existing Conditions performed an architectural survey of the façade, rotunda and courtroom of the building utilizing technologically advanced laser scans and drones demonstrating the power of the technology to produce accurate building measurements through reality capture and building documentation. Essentially, they were able to generate a digital version of the built environment in and around the building.

The company’s small and lightweight laser scanning equipment gathered real-time measurements and precise building information from the site in mere minutes.

Collected data and visualizations allowed the company to create as-built drawings from point clouds that provided a detailed understanding of the building as actually constructed versus how the building was designed.

In reality, as very few buildings are perfect manifestations of their original construction documents, field data was imported into drafting programs like Revit and AutoCad to generate detailed floor plans, roof plans, exterior elevations, reflected ceiling plans and MEP plans. The multiple types of construction-grade surveying equipment employed by Existing Conditions were non-disruptive and posed no threat to any visitors, artwork or the building itself.

About Existing Conditions: Founded in 1997, Existing Conditions was created to deliver high-quality documentation more accurately, efficiently and cost effectively than anyone else in the market. They have stayed true to their founding principles and continue to excel at leveraging reality capture technologies to deliver the most comprehensive building documentation.

Over the past 23 years, EC has measured and documented an estimated 200 million square feet of space for architects, engineers, building owners and real estate professionals and served clients and projects across the entire United States.